In the chemical age of agriculture that began in the 1960s, potassium chloride (KCl), the common salt often referred to as potash, is widely used as a major fertilizer in the Corn Belt without regard to the huge soil reserves that were once recognized for their fundamental importance to soil fertility. Three University of Illinois soil scientists have serious concerns with the current approach to potassium management that has been in place for the past five decades because their research has revealed that soil K testing is of no value for predicting soil K availability and that KCl fertilization seldom pays.

U of I researchers Saeed Khan, Richard Mulvaney, and Timothy Ellsworth are the authors of “The potassium paradox: Implications for soil fertility, crop production and human health,” which was posted on October 10th by Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems.

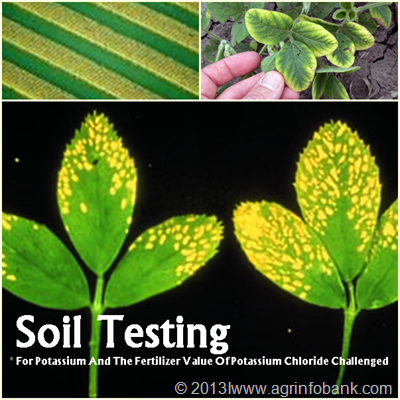

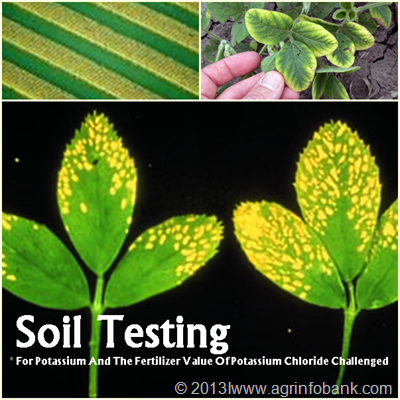

A major finding came from a field study that involved four years of biweekly sampling for K testing with or without air-drying. Test values fluctuated drastically, did not differentiate soil K buildup from depletion, and increased even in the complete absence of K fertilization.

Explaining this increase, Khan pointed out that for a 200-bushel corn crop, “about 46 pounds of potassium is removed in the grain, whereas the residues return 180 pounds of potassium to the soil—three times more than the next corn crop needs and all readily available.”

Khan emphasized the overwhelming abundance of soil K, noting that soil test levels have increased over time where corn has been grown continuously since the Morrow Plots were established in 1876 at the University of Illinois. As he explained, “In 1955 the K test was 216 pounds per acre for the check plot where no potassium has ever been added. In 2005, it was 360.” Mulvaney noted that a similar trend has been seen throughout the world in numerous studies with soils under grain production.

Recognizing the inherent K-supplying power of Corn Belt soils and the critical role of crop residues in recycling K, the researchers wondered why producers have been led to believe that intensive use of KCl is a prerequisite for maximizing grain yield and quality. To better understand the economic value of this fertilizer, they undertook an extensive survey of more than 2,100 yield response trials, 774 of which were under grain production in North America. The results confirmed their suspicions because KCl was 93 percent ineffective for increasing grain yield. Instead of yield gain, the researchers found more instances of significant yield reduction.

The irony, according to Mulvaney, is that before 1960 there was very little usage of KCl fertilizer. He explained, “A hundred years ago, U of I researcher Cyril Hopkins saw little need for Illinois farmers to fertilize their fields with potassium,” Mulvaney said. “Hopkins promoted the Illinois System of Permanent Fertility, which relied on legume rotations, rock phosphate, and limestone. There was no potash in that system. He realized that Midwest soils are well supplied with K. And it’s still true of the more productive soils around the globe. Potassium is one of the most abundant elements in the earth’s crust and is more readily available than nitrogen, phosphorus, or sulfur. Farmers have been taught to think that fertilizers are the source of soil fertility—that the soil is basically an inert rooting medium that supports the plant.”

Khan and his colleagues pointed out that KCl fertilization has long been promoted as a prerequisite for high nutritional value for food and feed. To their surprise, they found that the qualitative effects were predominantly detrimental, based on a survey of more than 1,400 field trials reported in the scientific literature. As Khan explained, “Potassium depresses calcium and magnesium, which are beneficial minerals for any living system. This can lead to grass tetany or milk fever in livestock, but the problems don’t stop there.

Low-calcium diets can also trigger human diseases such as osteoporosis, rickets, and colon cancer. Another major health concern arises from the chloride in KCl, which mobilizes cadmium in the soil and promotes accumulation of this heavy metal in potato and cereal grain. This contaminates many common foods we eat—bread, potatoes, potato chips, French fries—and some we drink, such as beer. I’m reminded of a recent clinical study that links cadmium intake to an increased risk of breast cancer.”

While working in the northwestern part of Pakistan three decades ago, Khan was surprised to discover another use for KCl fertilizer. “I saw an elderly man making a mud wall from clay,” Khan said. “He was using the same bag of KCl that I was giving to farmers, but he was mixing it with the clay. I asked why he was using this fertilizer, and he explained that by adding potassium chloride, the clay becomes really tough like cement. He was using it to strengthen the mud wall.”

“The man’s understanding was far ahead of mine,” continued Khan, “and helped me to finally realize that KCl changes the soil’s physical properties. Civil engineers know this, too, and use KCl as a stabilizer to construct mud roads and foundations.” Mulvaney mentioned that he had demonstrated the cementing effect of KCl in his soil fertility class, and that calcium from liming has the opposite effect of softening the soil. He cautioned against the buildup philosophy that has been widely advocated for decades, noting that agronomic productivity can be adversely affected by collapsing clay, which reduces the soil’s capacity to store nutrients and water and also restricts rooting.

Khan and Mulvaney see no value in soil testing for exchangeable K and instead recommend that producers periodically carry out their own strip trials to evaluate whether K fertilization is needed. Based on published research cited in their paper, they prefer the use of potassium sulfate, not KCl.

Source: University of Illinois College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences

.jpg)